“Buen Vivir,” which means “Good Life,” is a word derived from the indigenous South American way of thinking. It refers to living in harmony with the environment and in spiritual richness, and was written into the Constitution of Ecuador in 2008. Since then, it has come to be used around the world, especially in Latin America, as a philosophy that relativizes capitalist “affluence.

Shoko Sugawara, owner of Kyokusen Book Shop, writes, “Survival in the true sense of the word cannot be achieved simply by surviving”*.

Survival in the true sense of the word – that is the question that many people seem to be asking more than ever in this pandemic disaster. So we began by asking various people what kind of “vague anxiety” and “unfounded hope” they are in as of 2021. We will try to put them all over this garden of curves. And in the store, we have lined up things that the members who lived in Mexico felt “buen vivir” there. All of them are forms of various practices in daily life.

- Excerpt from “The place that grows thick” by Takumiko Sugawara, essay for the June 2021 issue of Gunzo.

The large garden surrounding the curving store is like a hole in the city of Sendai Hachiman. Various plants and trees change their expressions throughout the year. We like to gather here. We have been spending more and more time casually in this garden, holding book readings, setting up a free library, drinking tea, and thinking. Because of the rare location of the “bookstore garden,” which is not a park, not on the street, and not a coffee shop, we can talk from a different perspective than usual. I even feel reassured that I have a “place” in the city of Sendai.

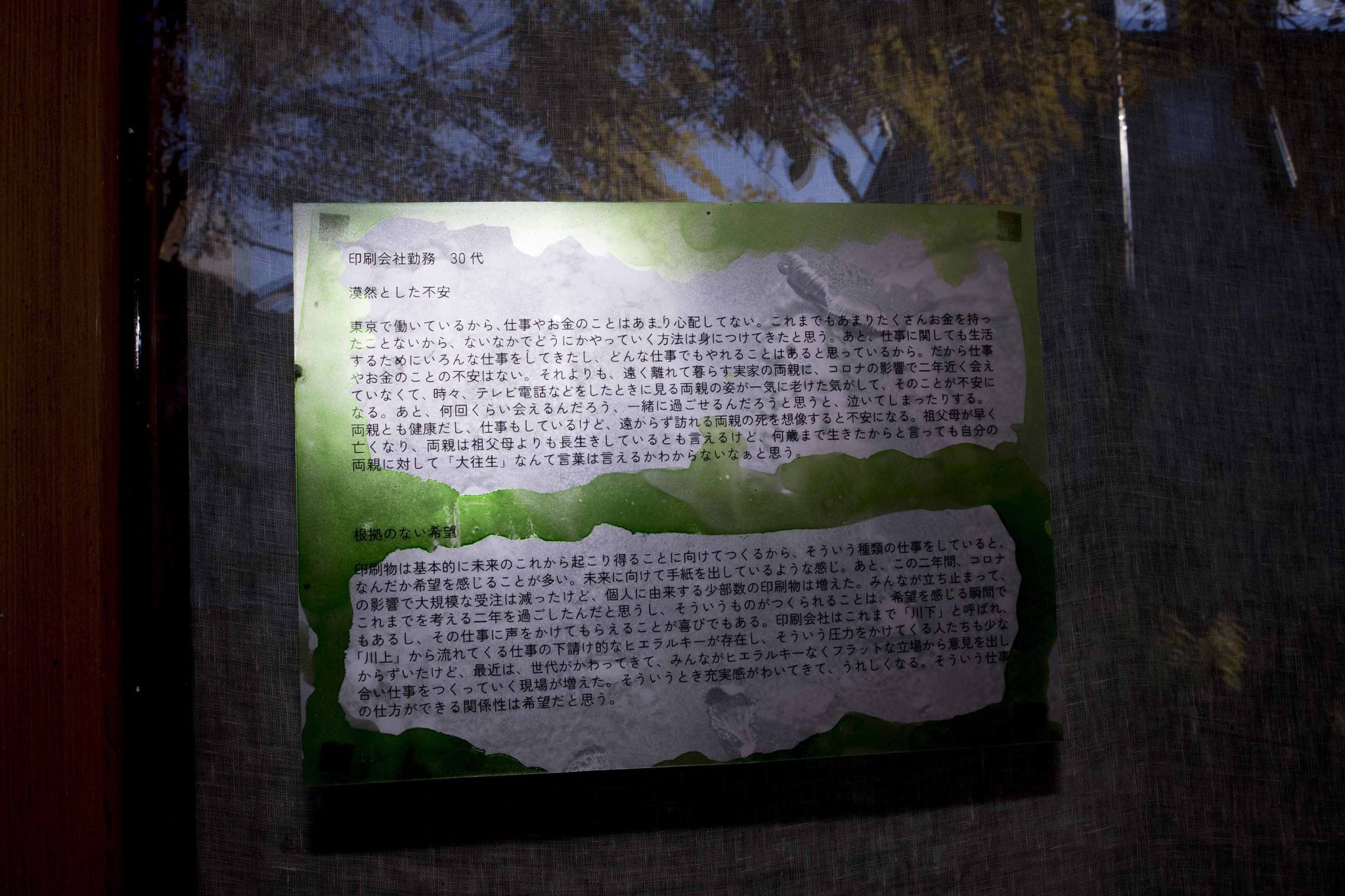

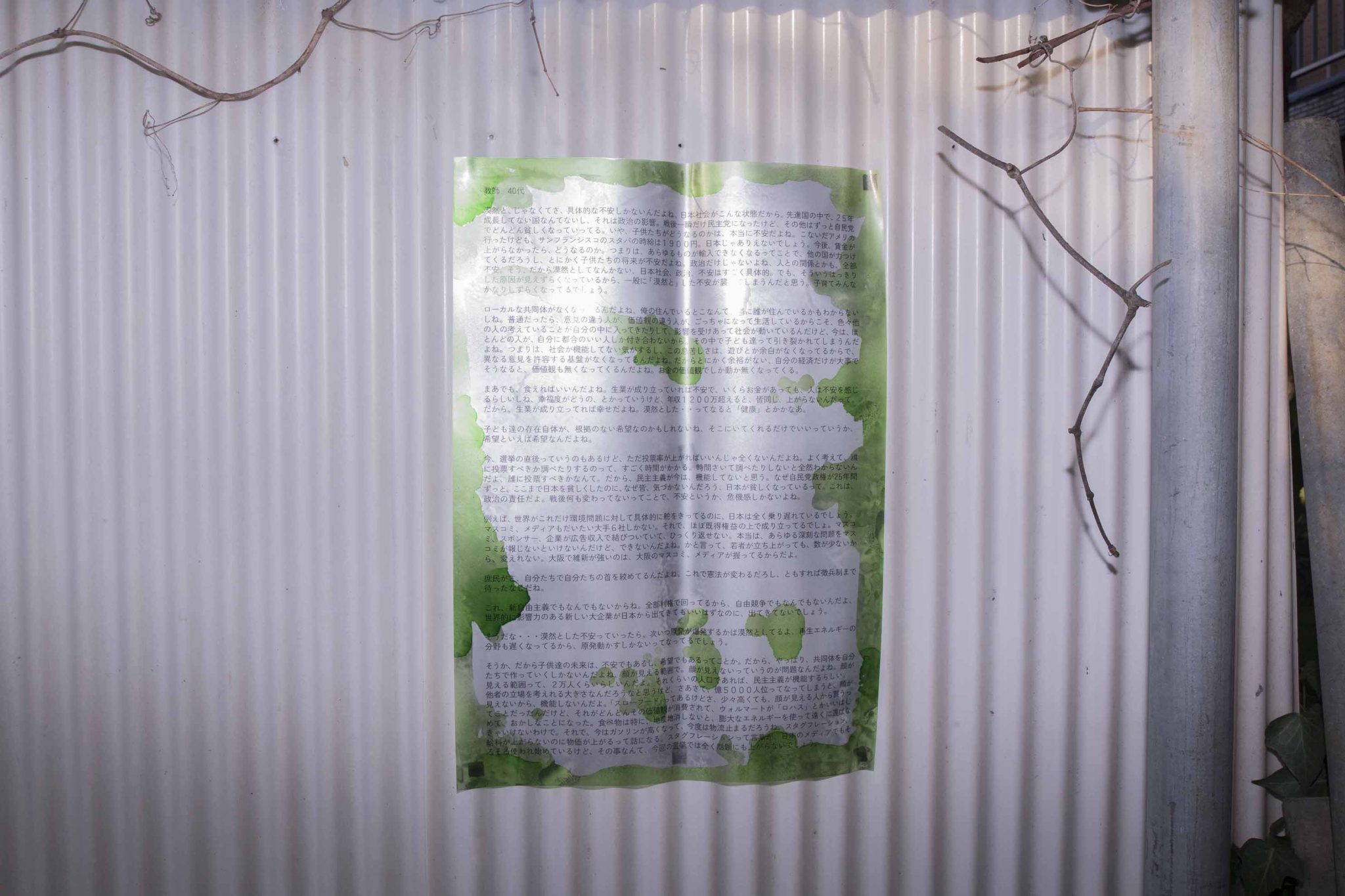

I thought I would consider such a simple but fundamental question as how we are living in today’s modern Japanese society, as a raw sense of each of us, including the feelings revealed by the oppression caused by the Corona disaster. We assume that the disquieting atmosphere in our society and the oppression that we have become so unconscious of that we cannot feel it are caught between the “vague anxiety” that we usually have and the “unfounded hope” that we feel like we can do our best, and the members of Pump Quakes have been asking people of various ages and backgrounds about their experiences. Friends from different backgrounds were interviewed about such fears and hopes. The 12 responses gathered were displayed throughout the garden in the autumn sunlight.

In fact, the answers to “vague anxiety” were often not vague. In other words, most of the things they were anxious about were clear anxieties, and most of them had clearly identified ways to deal with them. Creating a secure life is equal to life, and so on. On the other hand, even in such cases… where a person suffers from a serious social problem that is too much for one person to handle, the ideal solution has been played out, but to implement it, you have to change your job, your life, your relationships, all of these things, to the point where you have to change everything! Because we are faced with difficulties, we are just unable to take action, and it becomes painful. To our surprise, however, our close friends who answered the question began to talk about it in a different way than they usually do, telling us about a side of them that we did not know they were thinking about or worried about deep inside. Even if we could not solve the problem concretely, it might be enough just to talk to each other like this. Maybe what is needed is a tuning of feelings in individuals. If so, the response to the question of “unfounded hope” was not a feeling of the opposite of the anxiety expressed, but rather, in many cases, a more subtle sense of being alive, something that arises inside each person in the course of their normal lives. The gradation between these two questions. Perhaps there is a time of life here that we should deeply reconsider.

The practice of “buen vivir” is the lived experience of living our daily lives in a place that doesn’t separate us from our thoughts. The light and shadows on the walls, the scratches on the floor and walls, the light coming through the windows… When such traces trigger and remind us of every day, every vanishing feeling, we feel as if the marginal time of life between “vague anxiety” and “unfounded hope” begins to make sense.

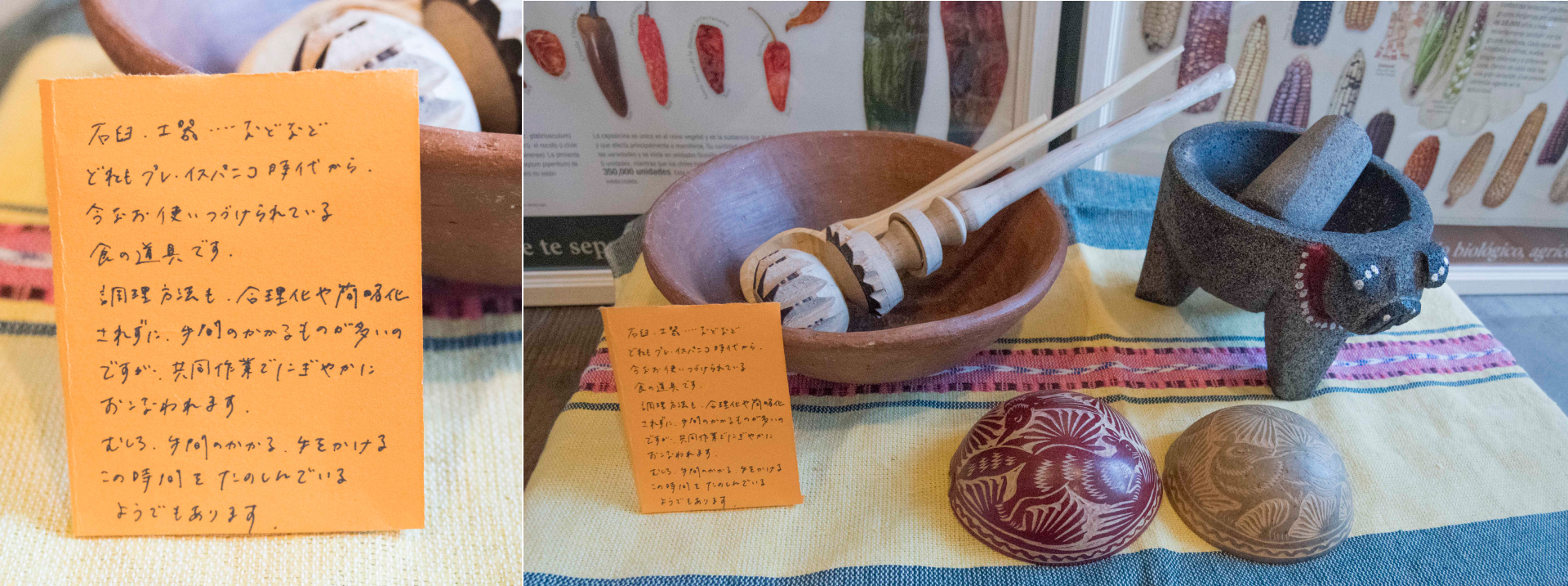

Meanwhile, inside the Curved store, Pampquakes members Chinatsu Shimizu and Yoshimiki Nagasaki displayed tools from daily life that they brought back from Oaxaca, Mexico, as well as the work of local artists supporting Buen Vivir, with captions by Shimizu. Each of the tools were all produced by human hands, and although they are artesanía, or crafts, they are not labeled and formal, but rather items that have been used by ordinary people on a daily basis for a long time.

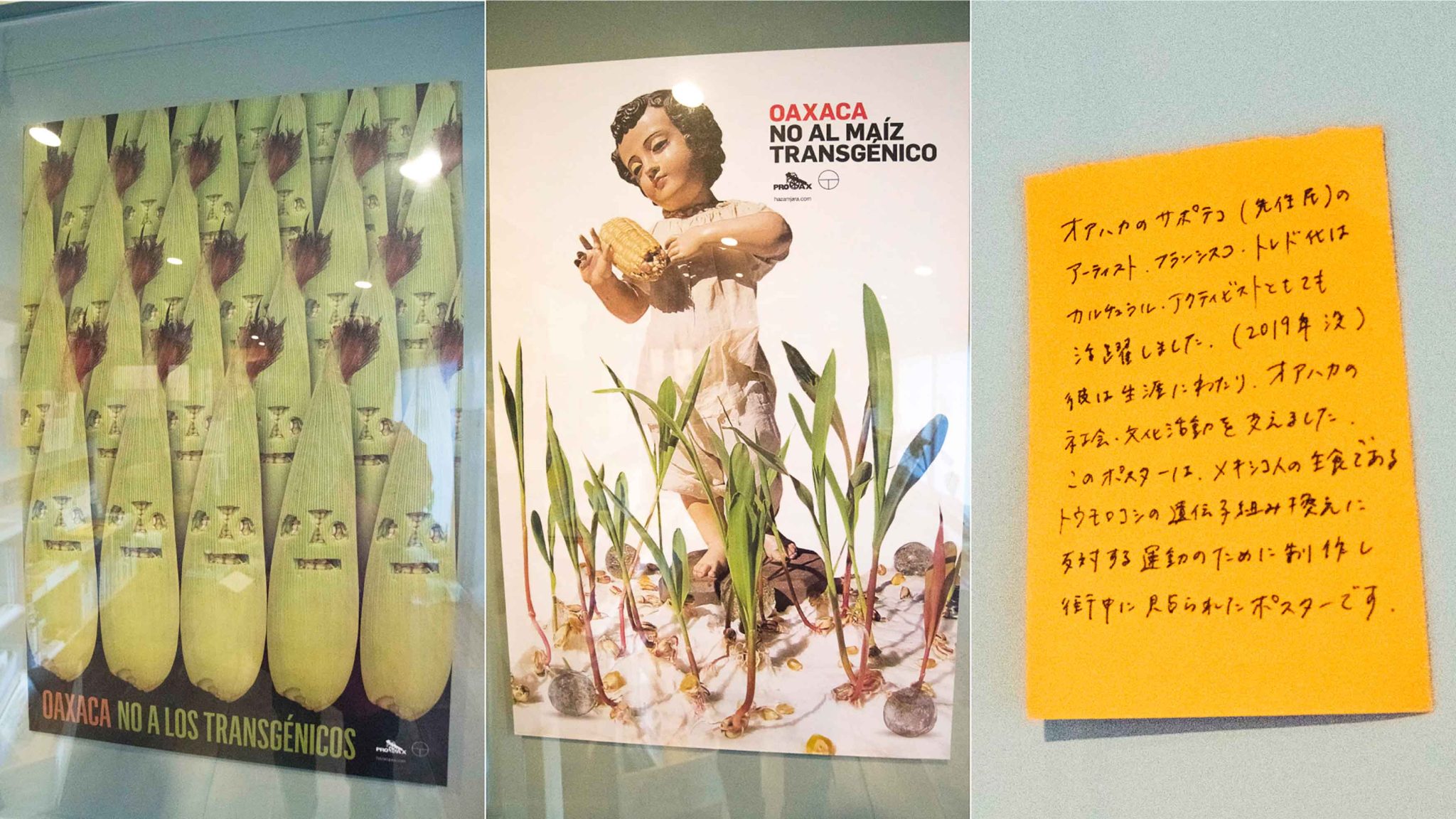

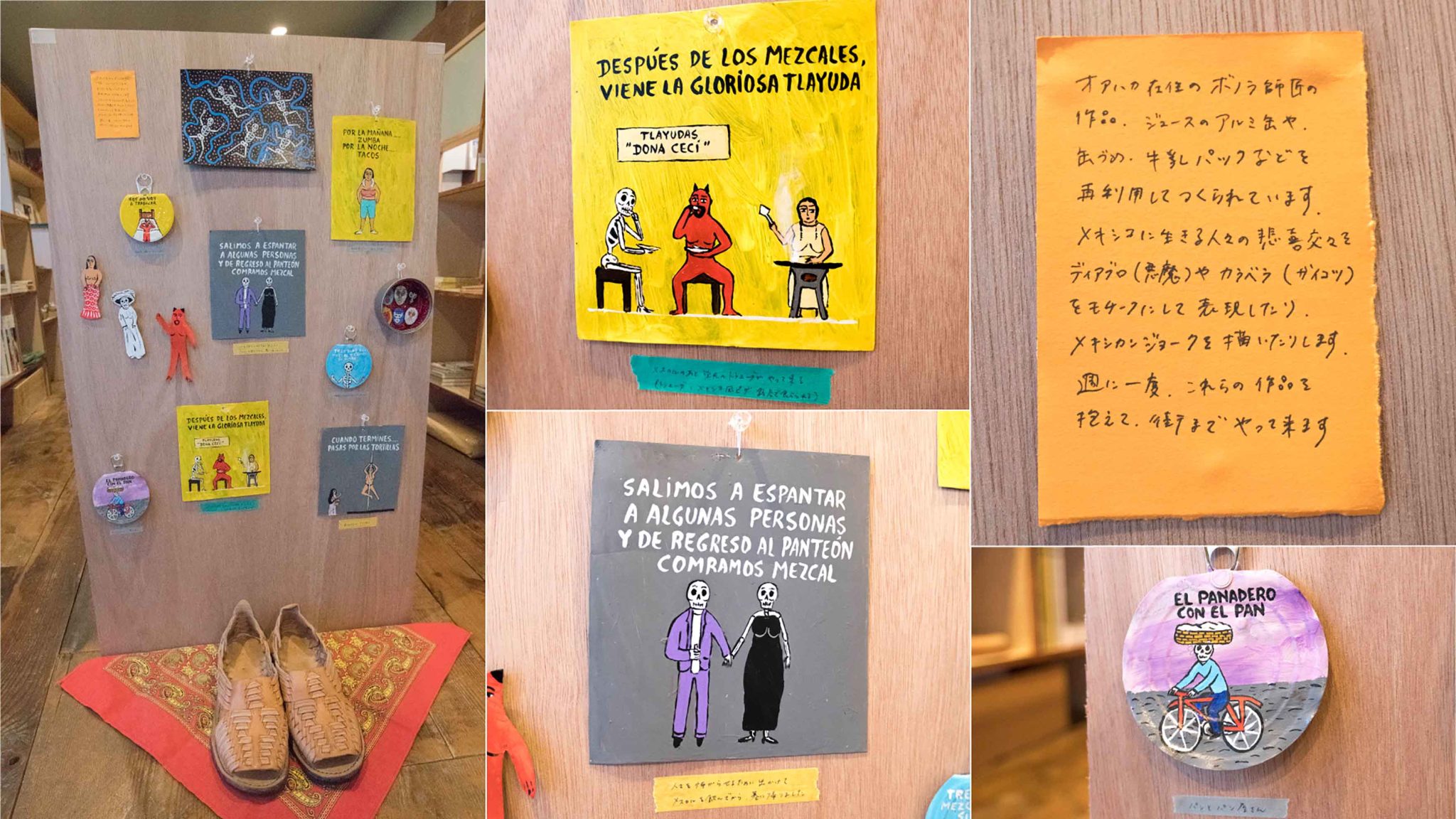

Two posters hanging on the walls oppose the genetic modification of corn, the basis of Mexican cuisine, and were created around Francisco Toledo, who passed away in 2019. Also on display were prints by ARMARTE, a collective of women who resist patriarchal capitalism, and works by Bonora, who portrays everyday Mexican life with a unique sense of humor by bricolaging milk cartons, empty cans, and other materials discarded from daily life.

Life in Oaxaca may be seen as poor and difficult from the capitalist side, but each tool carries the history of the common people’s lives and embodies the happiness and values they choose. The artists are working to ensure that these lives are not undermined by voices from the outside.

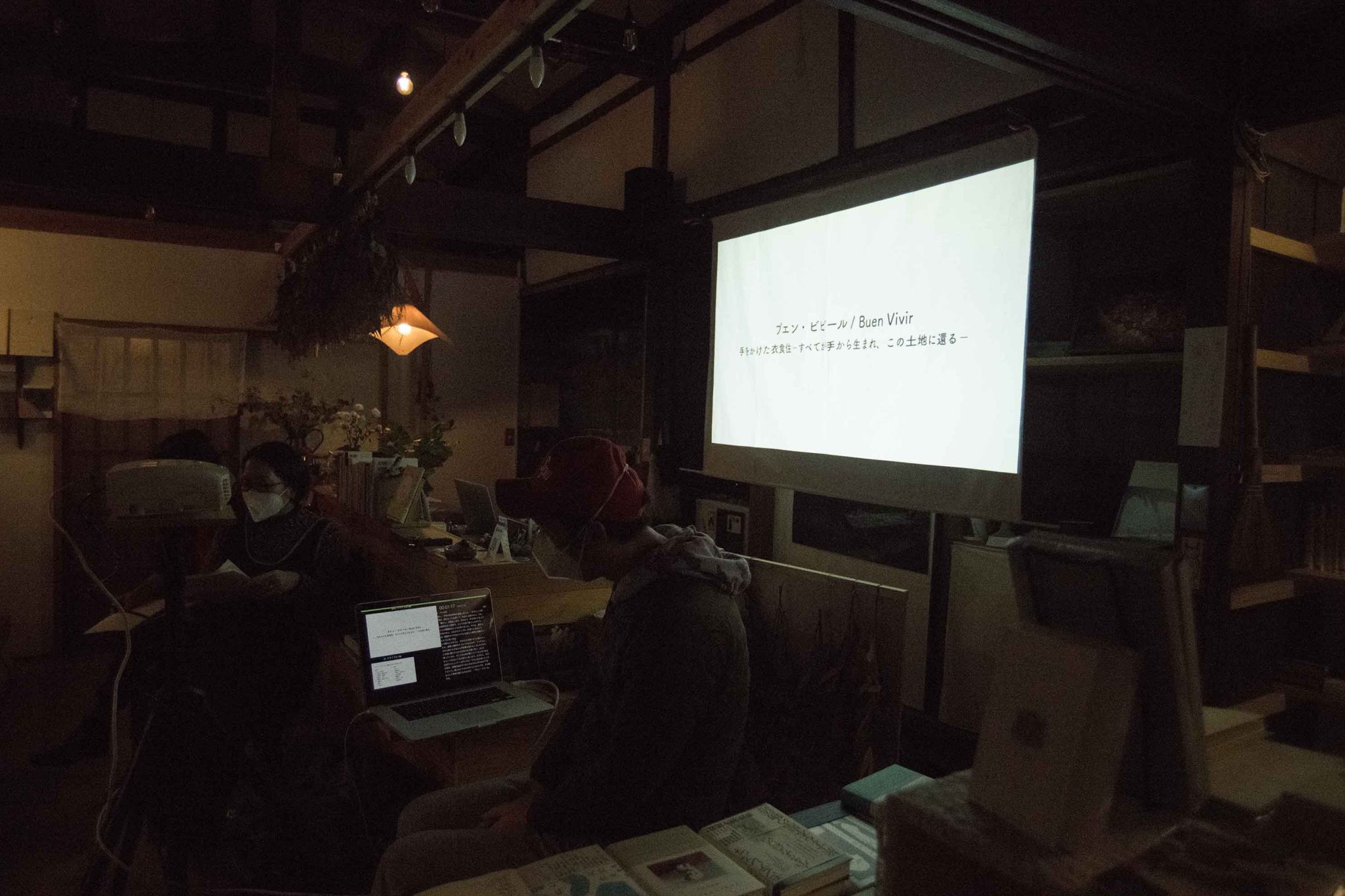

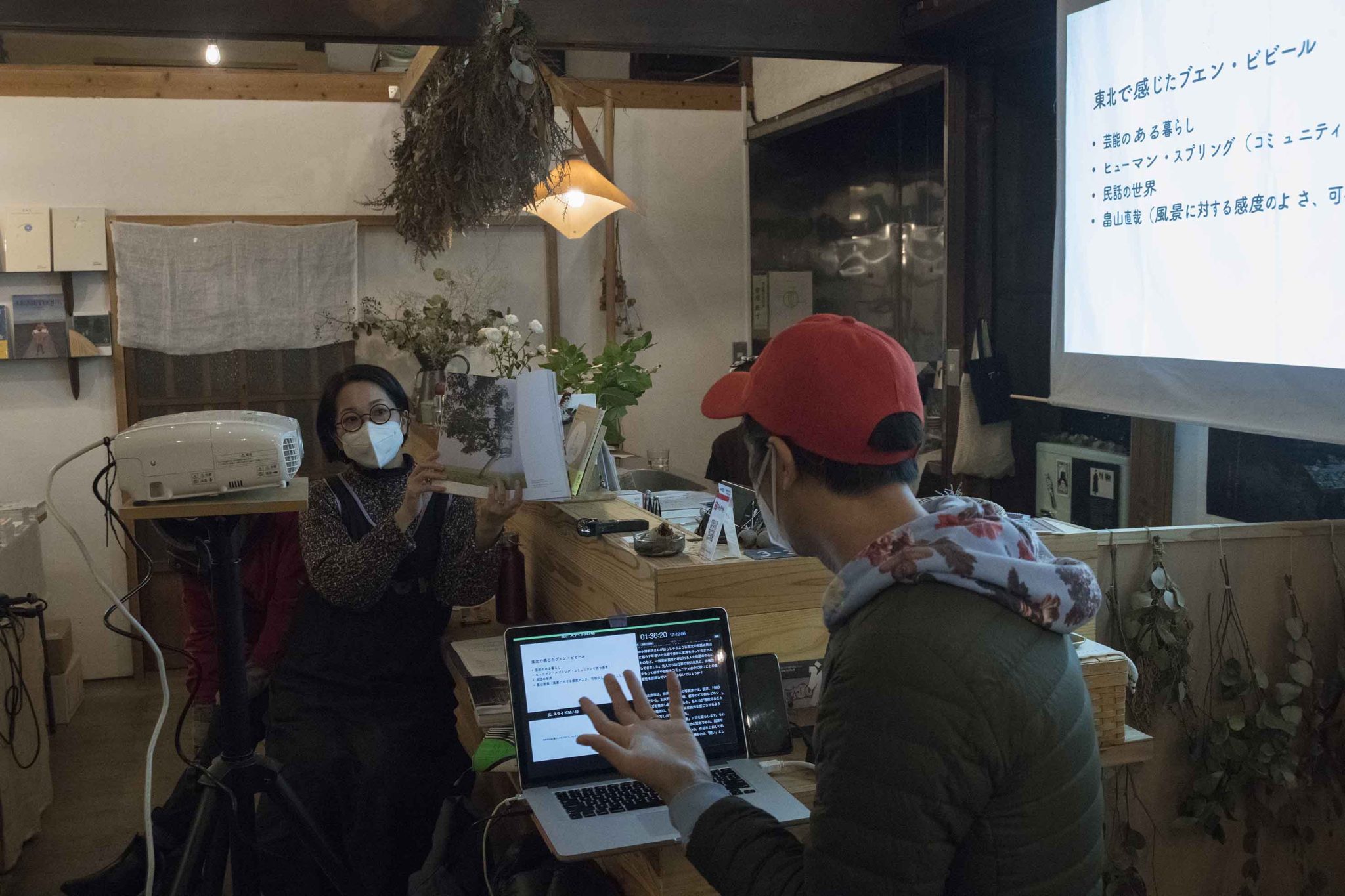

On November 23, the last day of the exhibition, Shimizu and Nagasaki held a talk event titled “Handmade Food, Clothing, and Housing: Everything is born from hands and returned to the land,” which was facilitated by Shiga.

First, he shared the concept and background of the term “buen vivir,” and then introduced the things that they themselves actually felt “buen vivir” in Oaxaca.

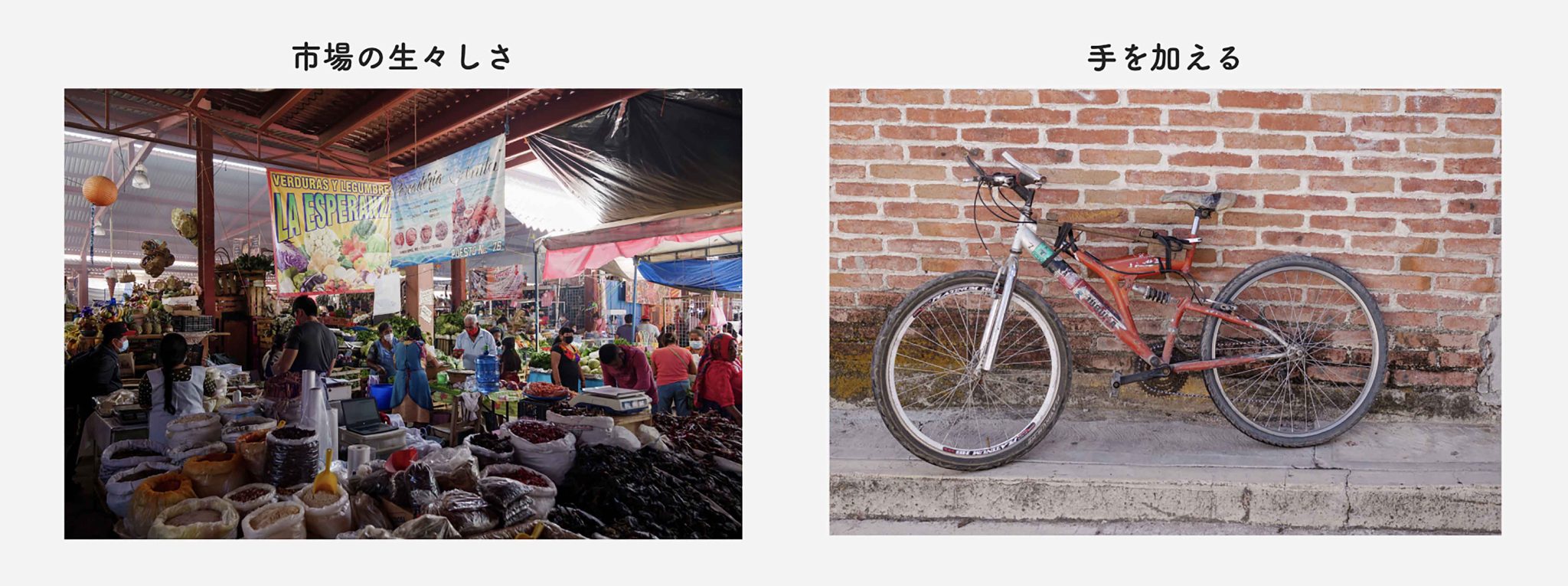

In Oaxaca, there are many markets where all kinds of things related to food, clothing, and shelter are sold, and we can understand sensibly where they originated and through whose hands they arrived. And then they are returned to the land by human hands, where they are used to their fullest.

One artist (she combines embroidery, printmaking, and letterpress) said, “Take your time. Slow creates space.” This quote led to a discussion about the slowness of time.

Finally, referring to Yoshihiro Nakano’s text, “Regionalism as ‘Southern-style knowledge’: Where Commons Theory and Theory of Common Sense Meet,” the group discussed how they would like to find and practice their own “buen vivir” in the future.

I believe that this attempt, through the exhibition and talks, served as a modest exercise in reexamining our own lives and setting up “buen bibir (good life)” on our own scale, unaffected by any external yardstick.

I would like each of you to imagine “Buen Bibir” from your own feet. Perhaps “buen vivir” can also be translated as “survival in the true sense of the word.

Grant : Sendai Cultural Foundation